By: Adrienna Wong

Erica Smith was making a fresh start. After being forced out of her home by domestic violence, she had spent the last three years cycling between homelessness and jail for petty offenses. But with the help of reentry organization Starting Over Inc., she finally secured stable housing and a job helping women who had experienced challenges like hers. She found community support in the Riverside chapter of All of Us or None. She was building a better life for herself and her daughter.

Then her employer got the notice: the state was trying to garnish her wages for unpaid court debt. Erica was confused. She had served her time – hadn’t she already paid her debt? Erica then discovered that she owed thousands of dollars in administrative fees related to her old court cases: booking fees, citation processing fees, conviction assessment fees. The court had been sending the collection notices to her old address, where she hadn’t lived for years. When she didn’t respond (because she never saw the notices), the court just kept tacking on additional fees for “failure to pay.”

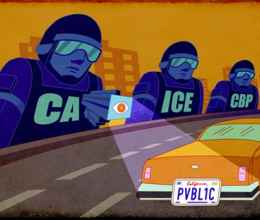

Every day, hundreds of thousands of Californians like Erica face bills for a multitude of fees attached to every stage of the criminal system: public defender fees, probation supervision fees, fees for mandatory drug tests, and electronic ankle monitors. When people can’t afford to pay off all their fees immediately, they are billed for even more: installment account fees, collection fees, interest, then assessments for “failure to pay.”

Although the people haunted by such fees experience them as a second punishment, that’s not what they’re supposed to be. The fees are imposed in addition to the fines, labor, and/or incarceration that the court assigns to a convicted person as punishment. Fees exist to generate revenue for government programs.

For decades, some politicians have tried to fill the state’s coffers using the criminal system in this way – with money made off the backs of the most vulnerable Californians. This method of generating revenue is, in the words of a recent New York Times columnist, “downright depraved.” It is also hopelessly inefficient.

Fees are an unreliable source of revenue. The vast majority of people who owe fees simply cannot afford to pay them. As a result, collection rates are low; counties sometimes end up spending more to collect fees than they bring in. For example, in 2017, Alameda County had a collection rate of only 4% for probation supervision fees. The county lost $1.3 million dollars trying to collect court-ordered debt.

Even when people manage to scrape together payments, it comes at great cost. While people struggle to pay off their fees in installments, the outstanding debt continues to harm their credit and limit employment opportunities, which in turn makes it harder for them to secure the means to pay. Entire families must choose between debt payments and necessities like rent, groceries, or health care. A study by the Ella Baker Center found that family members, usually mothers and wives, end up paying criminal system debt. In all these ways and more, fees put pressure on the social safety net and create devastating barriers for people at the exact time they’re trying to get their lives on track.

The burden of these fees falls heaviest on Black and brown communities, who are over-surveilled, over-policed, over-arrested, over-convicted, and whose members spend disproportionately more time on probation and parole. The criminal fees system worsens the racial wealth gap, dividing Californians along lines of class and race in ways that harm us all.

But California has an opportunity to unite to forge a more just and equitable path. This year, State Senator Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles) introduced SB 144, the Families Over Fees Act, to “remove the economic shackles” of administrative fees. The bill, sponsored by the Debt Free Justice California coalition, would eliminate a wide range of fees.

It’s time for California to find a more just and sustainable way to finance government – one that enables all Californians to thrive. Let’s start by passing SB 144.

You can do your part to make sure the California Legislature passes SB 144: contact your state representative and ask them to vote YES on SB 144 to give Californians a fighting chance to succeed.

Adrienna Wong is a staff attorney with the ACLU of Southern California.

-->