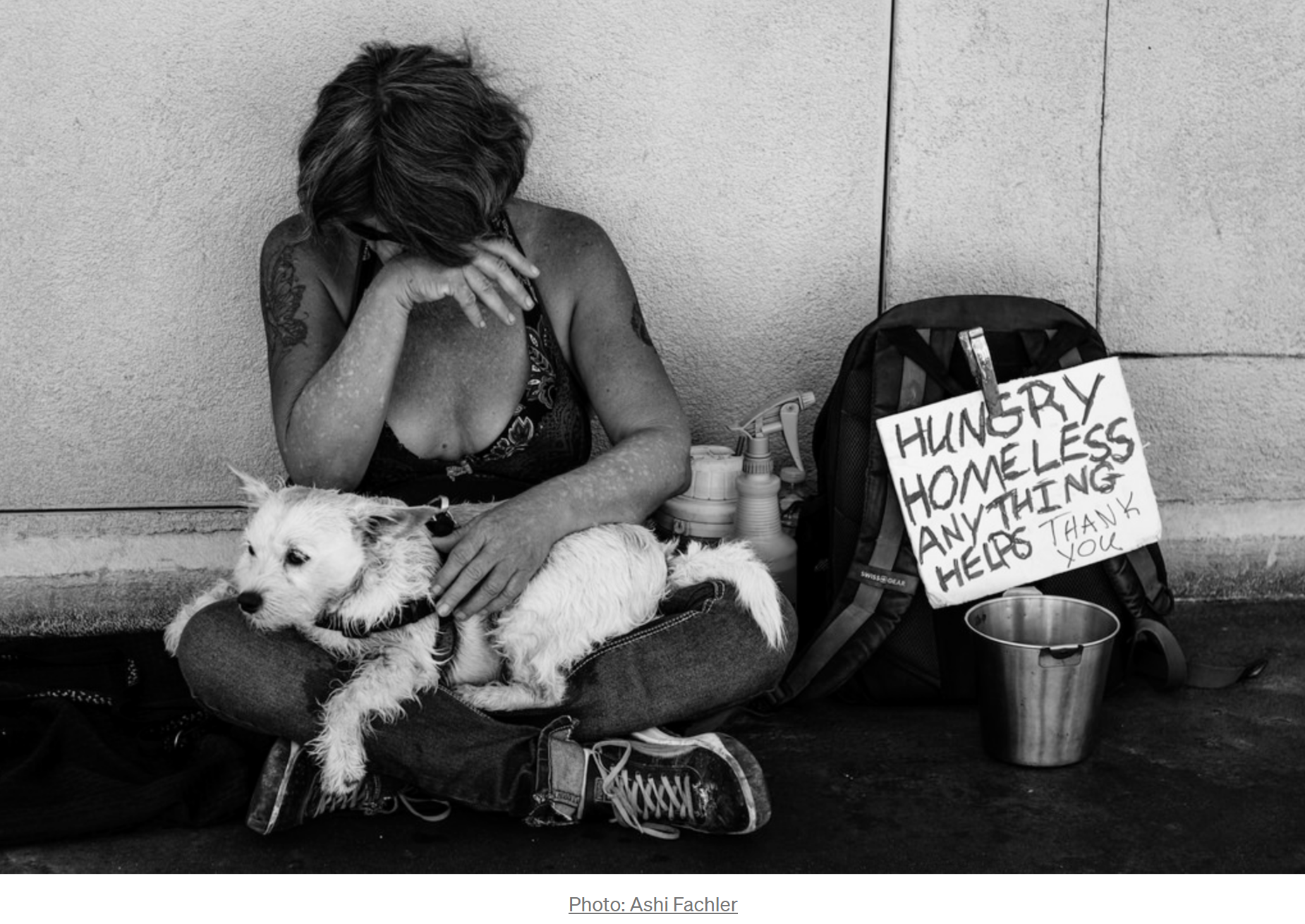

There are ways to address homelessness that are compassionate, humane and just.

By Anne Rios

Criminalizing poor and homeless people for engaging in basic life-sustaining activities like eating, sleeping, resting and seeking shelter is unjust and cruel. It entrenches people in homelessness. When it’s done under the auspice of a vague and biased ordinance, it adds insult to injury.

In March, ACLU of San Diego and Imperial Counties and Think Dignity filed an amicus brief in the case of a man cited for allegedly living in his truck. The man’s defense attorney, Think Dignity and the ACLU say the law he is accused of violating is vague, discriminatory and unconstitutional.

On Sept. 21, 2016, a San Diego police officer issued the citation after he said he saw Tony Diaz sleeping in a pickup truck that parked in the Bonita Cove area of Mission Beach. Diaz challenged the citation but lost.

Today, the court heard arguments in the appeal. It’s a case that deserves special scrutiny because it calls attention to the way in which we address this vexing problem in our region.

The growing number of homeless people in San Diego is staggering and shameful. Just two years ago, there were an estimated 8,692 homeless people in the region. Now, there are close to 10,000 people without permanent housing.

What we are doing, whatever San Diego is doing, to end homelessness simply isn’t working. And criminalizing the poor and homeless as many cities, including San Diego, have done certainly doesn’t help.

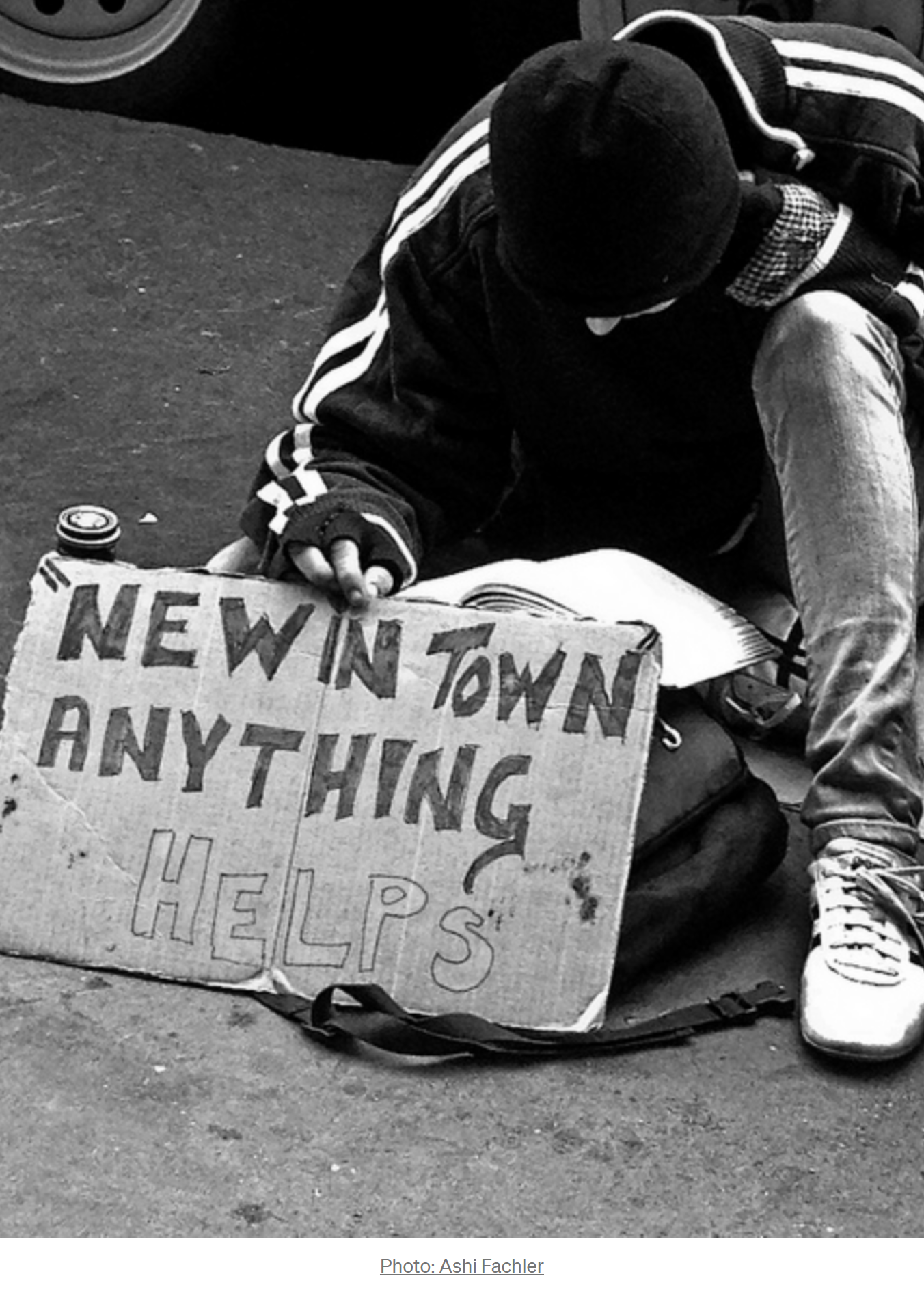

A web of systemic oppression is created when people can be cited, fined, or even arrested because they have no place to go. It’s counterproductive because it makes it even more difficult for people to get a job and get a home. It perpetuates the cycle of homelessness.

The list of laws criminalizing the homeless is long and it keeps growing. Whether it be illegal encroachment, illegal lodging, or banning the use of a vehicle as shelter — there is simply no relief.

The prohibition against staying in a vehicle is especially egregious because it strips an individual of their very last bit of refuge. That’s what got Diaz in trouble.

But the way this ordinance is written is so vague that it invites unequal application. It fails to provide adequate notice of the conduct it prohibits and it encourages arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement.

Authorities may claim that the law applies to all — whether rich or poor — but its effects are felt only by the poor, even though both may engage in similar behavior. The only ones criminalized by this ordinance are the poor and the homeless because the rich don’t need to sleep under a bridge or inside a vehicle.

When we have an ordinance that is solely directed towards one group of people, don’t we have a duty to question its motives?

Today, we asked the court to protect justice and uphold the Constitution by striking down this law, which is nothing more than thinly disguised bias and prejudice.

We asked that the court reverse the earlier decision of the trial court and rule that the City of San Diego’s vehicle habitation ordinance is unconstitutional.

Using what little people have as a shelter is not ideal. It’s not preferable. It’s not what those of us with a home would do.

But I ask: What’s a better alternative? The streets? Where one is exposed to the elements — excessive heat during summer and cold during winter? Where last year people were dying because of a Hepatitis A outbreak? Where the year before, people were being attacked and murdered because they were homeless?

There are ways to address homelessness that are compassionate, humane and just. Prohibiting the use of their vehicles as shelter is not one of them. It is beneath the dignity of the residents of this great city and it is not the answer to our homeless problem.

Anne M. Rios is executive director of Think Dignity.

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.