“The appetite grows for what it feeds on.”

By Jonathan Markovitz

When crusading journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells published an editorial in the Memphis Free Speech on May 21, 1892, challenging the most popular political justification for lynching by declaring that “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old threadbare lie that negro men rape white women,” she struck at the heart of white supremacy. A writer for another local paper, assuming that the author of the unsigned editorial was a man, called for his castration, and the Free Speech’s office was destroyed by a mob when Wells was out of town.

In the decades following the Civil War, the myth of the “black brute rapist” was not only a viciously racist stereotype with dehumanizing power sufficient to mobilize white mobs, often numbering in the hundreds or thousands, to attend and partake in massive extralegal public spectacles resulting in the complete destruction of an individual’s body. (“The nineteenth century lynching mob cuts off ears, toes, and fingers, strips off flesh, and distributes portions of the body as souvenirs among the crowd,” wrote Wells.) It was also an incredibly potent symbol that provided the ideological foundation for systems of oppression that denied African Americans anything approaching full equality. So long as Black men were understood as presenting an existential threat to Southern White Womanhood, the need for the continued subordination of African Americans was taken as a given in mainstream (white) Southern social and political discourse.

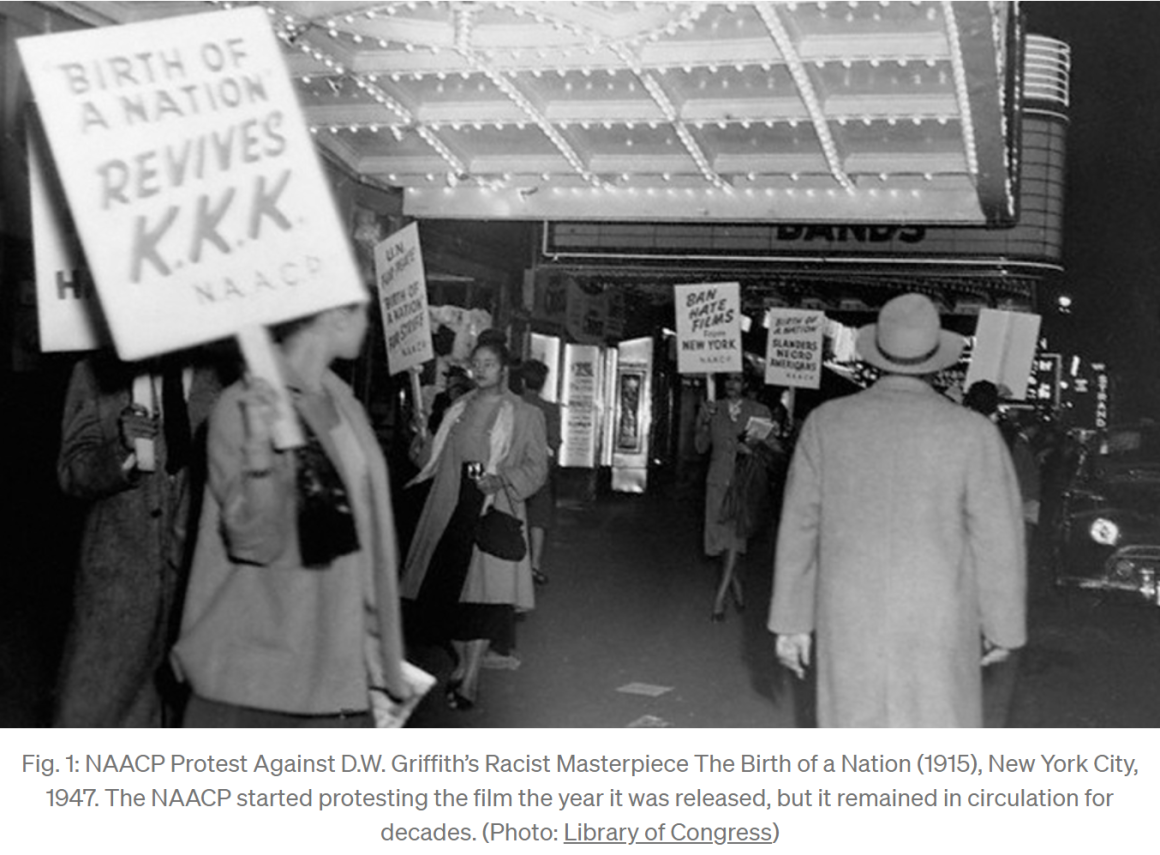

The black rapist myth was widely disseminated through virtually every part of American culture. It was featured prominently in newspaper editorials, in novels and plays, and even in pro-lynching ballads. It was the most galvanizing image in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of the Nation (1915) — the first feature-length film, which inaugurated the Hollywood studio system while glorifying the Ku Klux Klan, attracting millions of audience members, and inspiring the “Second Klan” of the 1910s and 20s. President Woodrow Wilson, who screened the film at the White House, was alleged to have said the film was “like history written with lightning.”

Most people in the United States are never taught about Ida B. Wells — an African American, or that she was an early member of a broad anti-lynching movement that fed into the modern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The anti-lynching movement’s size and strength varied over the years, as did its tactics. Activists disagree about all sorts of things, including such matters as whether to protest in the streets or fight for change by petitioning elected officials through letter-writing campaigns demanding federal anti-lynching legislation. The one thing that virtually everyone within the movement agreed upon, however, was that it would be impossible to bring an end to lynching so long as the racist myth that enabled it was allowed to go uncontested. Said Wells, “[t]he way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

By the 1930s, the myth of the Black rapist had been systematically hammered away at for over half a century, and Wells’ words about the inability to believe in the “threadbare lie” had become true for much of the nation and the world. Lynching could no longer exist as the defining feature of Southern race relations when the ideological foundation for the practice had been systematically exposed as nothing more than a fig leave masking the true barbarism of Southern society, which all too often came in the form of grotesque white supremacist violence.

It might be comforting to believe that this is all ancient history. But as William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” The mythical black rapist may not loom as large in the American political and cultural imagination as it once did, but it still has considerable and inescapable heft. It was mobilized with chilling effectiveness in the 1988 Presidential election, in the form of the infamous Willie Horton ad, which helped propel George H.W. Bush’s campaign. When stripped of its explicitly sexualized content, it becomes a figure of pure violent monstrosity, invoked by police officers as justification for killing a never-ending stream of unarmed black men, women, and children. (Just one example: Darren Wilson explained his shooting of Michael Brown by describing Brown as a “demon” with superhuman strength. There is no way to avoid the question of whether age-old myths of Black violence figured into the Grand Jury’s determination that Wilson’s fears were reasonable.)

It is not only Blacks who have suffered because of the real-life impact of fictional imagery. When an elderly white man named Anthony Simon shot and killed Steffen Wong, his Chinese American neighbor, while Wong was entering his own home in Kansas in 1981, Simon’s defense centered on his belief, based on nothing other than racist stereotypes of Asian Americans as dangerous martial artists, that Wong posed an imminent threat to his safety. Simon’s acquittal on all charges provided a clear indication that the jury was influenced by the same stereotypes that motivated Simon’s murderous act.[1] Similarly, widespread images of Latinos as violent gangbangers have led to numerous instances of anti-Latino violence where the assailants have faced little or no punishment, or have even been celebrated as vigilante heroes.[2]

And the issue isn’t just one of street-level violence. Instead, the ways that we think about and picture race can shape policy decisions affecting every aspect of contemporary life. The “New Jim Crow” of the criminal justice system would be inconceivable if not for the ubiquity of images of people of color as violent criminals, and our increasingly punitive and nativist immigration system is reliant on the appeal of Presidential references to Mexicans as “rapists” and to the entire continent of Africa as composed of “shithole countries.”

But this isn’t a one-way street. If racist imagery can lead to damaging real-life consequences, then anti-racist imagery can be an important part of fighting for social justice. The photo of Ieshia Evans (fig. 3) in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, that captured the attention of audiences around the world in the summer of 2016 is important not only because it highlights her grace, power, and vulnerability while suggesting that the forces of racist policing can be literally knocked back on their heels through non-violent protest, but also because it counters centuries-old racist depictions of Black women (as irrational, hypersexual, or inherently hostile, to name a few). Images like this can change prevalent understandings of Blackness, and can form the basis for popular acceptance of better public policies that would decenter racist policing and attempt to meet the real-life needs of communities of color.

[1] See Cynthia Kwei Yung Lee, “Race and Self-Defense: Toward A Normative Conception of Reasonableness,” 81 Minn. L. Rev. 367, 438 (1996) for a discussion of this case.

[2] See id. for examples.